Recently Paul Martens and Jonathan Tran of Baylor University “interviewed” me by email for forthcoming articles they are preparing for The Christian Century and The Other Journal, along with co-authors David Cramer and Jenny Howell. Their work seeks both to investigate and to reflect theologically on now-well-documented sexual abuse by John Howard Yoder, leading spokesman for Christian pacifism and Mennonite peace theology in the latter half of the twentieth century. Since I was a student of Yoder’s at the University of Notre Dame in the early 1990s as news of Yoder’s abuses emerged, Martens and Tran wanted to know about my experience with Yoder there. Their questions have allowed me to reflect — and now to go on the record — far beyond what they will want or need to quote. So with minor editing, I share my reflections here.

Recently Paul Martens and Jonathan Tran of Baylor University “interviewed” me by email for forthcoming articles they are preparing for The Christian Century and The Other Journal, along with co-authors David Cramer and Jenny Howell. Their work seeks both to investigate and to reflect theologically on now-well-documented sexual abuse by John Howard Yoder, leading spokesman for Christian pacifism and Mennonite peace theology in the latter half of the twentieth century. Since I was a student of Yoder’s at the University of Notre Dame in the early 1990s as news of Yoder’s abuses emerged, Martens and Tran wanted to know about my experience with Yoder there. Their questions have allowed me to reflect — and now to go on the record — far beyond what they will want or need to quote. So with minor editing, I share my reflections here.

1) Yoder’s extra-marital sexual activity – using this phrase loosely – was made public in 1992 through a series of articles published in The Elkhart Truth. That said, were you aware of these activities before or during your studies at ND?

Though I have now become Roman Catholic, anyone who knows me knows that I am very much a product of the Goshen-Elkhart Mennonite community, which has been a leading intellectual and institutional center for at least one branch of the Mennonite Church in North America. My father was on the faculty of Goshen College and was a leading historian of American Mennonites. My BA is from Goshen College and my MA is from the now-renamed Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary (AMBS) in Elkhart. Growing up we lived across the street from Guy F. Hershberger, who in his generation occupied something of the space as leading spokesman for Mennonite peace theology that Yoder later occupied in his generation. In fact my dad is Hershberger’s biographer. It goes on and on.

Not surprisingly, Yoder was influencing my theological development as a young Mennonite long before I went to Notre Dame. I started reading him in college, took his class on War, Peace and Revolution at AMBS in the fall of 1979, made use of his work in the crucible of Mennonite Central Committee work on peace and justice in Central America in the early 80s, and corresponded with him once or twice in those years. When I applied to do doctoral work at ND, he wrote me a recommendation, which I’m sure helped me get in there.

All of this is background for explaining how I started hearing inklings sometime in the mid-80s, probably within a year or two of when AMBS terminated its relationship to Yoder and he shifted to a full-time position at ND. My dad didn’t know details, I think, but he considered it important that I know what he knew – namely that there had been some kind of sexual impropriety, and that Yoder had been intransigent in the face of AMBS President Marlin Miller’s efforts to set boundaries and disciplines.

The latter point here is worth underscoring. Nothing nothing nothing that I say should imply that the sense of betrayal that started nagging me already in the 1980s, and that hit full-bore in the early 1990s, approximates the betrayal, pain, violation, and trauma of the women whom Yoder abused. But we didn’t know the extent of the violation at the time, and so what hit me then as a budding theologian was a sense that by stiff-arming AMBS, Yoder was at minimum failing to live up to the kind of believers-church accountability that was critical to his ecclesiology and his ecclesiocentric peace theology. Yoder’s writings had long conveyed a certain disdain for the flesh-and-blood Mennonite community as it is (see e.g. his essay from the mid-1960s or earlier, “Anabaptist Vision and Mennonite Reality”). And so – no doubt influenced by my dad but also my own reading – Harold S. Bender and especially Hershberger more than Yoder had already become my role models for what it meant to be a believers-church theologian who sticks with and serves the real not the ideal Church. (Draw a line to my becoming Catholic right there, if you want, and – go ahead, I get it – feel free to savor the various paradoxes.) What we started to learn about Yoder in the 1980s left me wondering: Was his own personal morality part of what had estranged him from the leadership of the Mennonite Church? Or was it somehow a symptom of his estrangement and unaccountability?

In any case, while I was and remain influenced by Yoder’s thought, I had my eyes open from pretty early on for what might be vitiating it. More on this below. When I applied to ND, it was not exactly to study with Yoder. Yes, his presence was a factor. But it was more that I was reassured I would be welcome as a Mennonite at a school that would have a Yoder there, or for a time, a Stanley Hauerwas. (I didn’t know until later about the degree to which Hauerwas had pretty much been driven out. That’s another story, and thankfully one that seems only ugly and not tragic.)

2.a) If you were aware of Yoder’s activities, how did you integrate this knowledge with your understanding of him as a teacher, scholar, and leader in the field of Christian ethics?

2.b) If you were not aware of these activities, when did you become aware of them? And, once you became aware of them, how did you reconcile them with the person you learned from at ND?

I don’t remember exactly when I learned what. But I was taking Yoder’s doctoral seminar on just war in the spring semester of 1991 (I think) when he told us we had to meet at a different time because he would be having regular meetings in Elkhart. These turned out to be the disciplinary meetings with Indiana-Michigan Mennonite Conference and Prairie Street Mennonite Church. Meanwhile I was going to church with, and lived fairly near to Tom Price, the Elkhart Truth reporter who eventually took the story public. Tom was professional enough to keep things under wraps, but I must have started getting hints or hearing rumblings about what he was working on. Because at some point I remember pretty distinctly approaching the female doctoral student in ethics whom I knew best. She was working with Yoder, I think, either as a grad assistant or on her dissertation. So I asked her what she knew – at least implicitly asking whether she’d experienced any improprieties, or knew of anyone else at ND who had. She hadn’t experienced anything, and I don’t think she knew of anyone else at least at that point. Apparently she had heard rumors (from AMBS? from ND? I don’t know) and had gone straight to Yoder and confronted him about “what’s this crap I’m hearing?” (She’s pretty no-nonsense, after all). Whether because he denied everything or because he satisfied her questions, this conversation led me to believe at the time that he was behaving at ND.

So while I was hearing rumblings, it was really the Elkhart Truth series that broke open the details and left me devastated. Soon afterward I went to the AMBS library and read the unpublished paper(s) that Yoder had written exploring some kind of new Kingdom sexuality bullshit. My full-bore sense of betrayal was now complete: Yoder had used his unsurpassed intellectual gifts to rationalize his own sins. Just about the only good to come of all this for me personally was the object lesson for a neophyte Christian ethicist: Learning ethics doesn’t necessarily make a person more ethical, for all the same skills one uses to analyze human agency and human actions can be turned into abject rationalization.

My relationship with Yoder after that was already pretty formal and it got even more so. I had decided on a different advisor, Jean Porter, already in my first semester. Yoder actually encouraged this, counselling me that I might get pigeonholed if I as a Mennonite worked with him. Then I got interested in Augustine, which I am sure disappointed him. He did serve on my dissertation committee but we rarely talked and he generally shared his comments on my chapters by way of Porter. For my part, I didn’t know how to approach him, or whether I wanted to, and then the longer it went, the harder it got. Since I was then a member of a Mennonite church in the regional conference that was disciplining him, I wondered if he thought I was shunning him. And then I wondered if in a way I actually was.

What is unclear relationally is clear intellectually though. Even while appropriating Yoder’s thought, I was all the keener to watch for ways in which his rationalizations might have crept into and vitiated his thought. As I read his generation of Mennonite thinkers generally (Concern Group specifically) and him in particular, I increasingly asked: Is this really Anabaptism talking, or the Bible as interpreted by Anabaptism, or is it Enlightenment liberalism clothed in an acceptable “Anabaptist” garb? My father had written of 19th-century revivalism that it provided Mennonites an acceptable conduit into the American mainstream. Similarly I now wondered whether for acculturating, newly higher-educated Mennonites in the 50s and 60s, the version of Anabaptism that Yoder and his generation had advocated was doing something similar – not taking them into the American mainstream per se, but letting them find a respectable place within the American intellectual mainstream where “freedom” and “conscience” are overriding values and critiques of Amerika could even be chic. These questions found their clearest expression in my paper in the Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics, “Continuity and Sacrament, or not: Hauerwas, Yoder, and Their Deep Difference” (more or less = chapter 2 in Unlearning Protestantism), which among other things takes on the approach of Yoder and the Concern Group to church authority and ordained ministry.

But here’s the excruciating dilemma that I think names how some of us can simultaneously feel such an abiding sense of debt to Yoder and an all-the-deeper sense of betrayal: There is simply no way to tell the story of 20th-century historic peace church theology – much less to appropriate it – without drawing on Yoder’s thought. So too with Christian pacifism more widely perhaps, but certainly Mennonite peace theology in particular.

Memory is starting to recede for younger peace church thinkers, I suppose, as they deal with what rightly or wrongly seem to them to be new questions. But the searing challenge for Mennonites in the 20th century was how to respond to the barbed compliment of Reinhold Niebuhr, acknowledging at last that they had gotten Jesus’ ethic right, but turning around and saying that they were thereby rendering themselves politically irrelevant and socially irresponsible. This after all was a sophisticated version of the existential accusation that very ordinary Mennonites who never read this stuff get thrown at them in every wartime – that they are shirkers. And no one responded to Niebuhr in more ways, through more decades, more trenchantly than Yoder. Guy F. Hershberger (War, Peace and Nonresistance) was starting to answer Niebuhr in the 40s and 50s, but even he relied on the young Yoder to clinch his arguments. In a later generation, someone like Duane Friesen had his differences with Hershberger and Yoder, but still relied heavily on Yoder’s formulations in, for example, Christian Witness to the State. Insofar as I remain a player in historic peace church debates as a “Mennonite Catholic,” Yoder’s work remains in the background even as I find more Catholic ways of making his most important points. And then there are all the new neo-Anabaptists who got their start by reading The Politics of Jesus.

So existentially I can understand the calls from younger Mennonite scholars to do peace theology without relying on Yoder. And if a middle course is at least to apply a hermeneutic of suspicion about the ways his patriarchy and worse might have shaped his theology, I’ve been doing this in my own way. But I just don’t see how they/we can do without him. But then another but: I’m all the more pissed at him for doing this to us, and the temptation rises to put aside my pacifism for 30 seconds and imaginatively slap him hard or wring his neck.

But then yet another but: I picture him and Annie going to a Lutheran church in Elkhart their last few years in part because – according to a close mutual friend who was one of John’s few confidants in those final years – he and Annie could receive communion regularly there. This, even though John’s theology never made much space for sacramental grace. Besides, he surely heard a robust Lutheran proclamation of God’s unmerited grace there. But … but … but …. Oh my. I am engulfed by a sense of tragedy and mercy and brokenness all around.

3) Recognizing that 2014 is not 1990, of course, how do you think ND should address this element of Yoder’s legacy (and it may be important to know that we have first- and second-hand account of Yoder committing at least sexual harassment while employed by ND). Admittedly, as a more recent graduate with a PhD from the Theology Department at ND, I [Martens] am not sure how to answer this myself…

I am least prepared to answer this question. But by way of comparison I know a few of the key players in the Catholic Church in Minnesota who have been trying to respond to the sex abuse crisis, and my sense is that they have been at their best when they have stretched the cautions of their lawyers as far as they possibly can or farther in order to put the victims first. I would hope ND could do the same. My worry is that since Yoder wasn’t a Catholic, much less a priest, ND will either see him as small potatoes and ignore victims, or see him and his legacy as an easy way to gain some credibility in the context of the larger continuing sex-abuse scandal and throw him posthumously under the bus. But by now I’m just speculating with a tinge of cynicism.

4) As professionals in the field of Christian ethics, how do you think the Society of Christian Ethics should address this legacy (as you know, Yoder was president of SCE in 1988).

Analogous to what I said about the excruciating dilemma that Mennonite theologians face because they can’t do without Yoder’s legacy but thus have been all the more betrayed by his actions, it certainly won’t do for the SCE to try to expunge his abiding influence. The dilemma may not be quite so excruciating or existential as it is for the Mennonite community, but it can’t be avoided. Rather, we should look for ways to name and ritualize the naming of the tragedy. If Yoder weren’t tied in relationship to us as part of the society, and if he weren’t such an abiding influence on some of us especially, his actions would be a scandal but not tragedy. We only feel betrayed by the very ones to whom we are most indebted, after all. Others for example might feel betrayed by Paul Tillich’s sexual abuse, but someone like me who is not a Tillichian in any way can feel scandalized but not betrayed. Whatever else the SCE does, we should name and ritualize and use our best gifts as ethicists to reflect on such a legacy in such a way that we go deeper into the tragedy not around it, and resist every temptation to avoid its pain — either by minimizing in any way the traumatic violation he has inflicted on some or by denying in any way the positive contributions he has made for others.

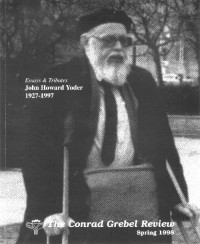

For myself, I have ritualized the naming of the tragedy with a photo of John on my wall. It is the cover of an issue of the Conrad Grebel Review, published soon after his death in 1997. The photo is of him making his way on the crutches he needed in this final years, as a result of a car accident and a foot wound that never healed. He still belongs on my office wall, simultaneously as an honor and as an object lesson, but in either case only there with sad recognition of a brokenness that he could never outlive and that I cannot forget, but must face.

23 April 2013

Also see follow-up commentary: Yoder and the limits of Matthew 18

Thank you, Gerald, for being willing to “go deeper into the tragedy and not around it.”

Thank you for this valuable testimony.

Your insights, as someone a bit more removed from this story than I am, are very helpful, Gerald. I particularly appreciate the notion of needing to “ritualize the naming of this tragedy”. As Mennonites we aren’t particularly skilled at creating rituals, but there is a depth of pain in this story that may only be touched and healed in nonverbal ways–through art, through music and dance, through rituals of lament and corporate keening.