For decades now, popes and episcopal conferences have been insisting that to work for peace is the vocation of all Christians. Too often, however, peacemaking seems the domain of special vocations or technical specialists. This is certainly not the church’s hope. As Pope John Paul II proclaimed in his World Day of Peace message at the opening of Jubilee Year 2000: “The church vividly remembers her Lord and intends to confirm her vocation and mission to be in Christ a ‘sacrament’ or sign and instrument of peace in the world and for the world. For the church, to carry out her evangelizing mission means to work for peace…. For the Catholic faithful, the commitment to build peace and justice is not secondary but essential” (No. 20).

For decades now, popes and episcopal conferences have been insisting that to work for peace is the vocation of all Christians. Too often, however, peacemaking seems the domain of special vocations or technical specialists. This is certainly not the church’s hope. As Pope John Paul II proclaimed in his World Day of Peace message at the opening of Jubilee Year 2000: “The church vividly remembers her Lord and intends to confirm her vocation and mission to be in Christ a ‘sacrament’ or sign and instrument of peace in the world and for the world. For the church, to carry out her evangelizing mission means to work for peace…. For the Catholic faithful, the commitment to build peace and justice is not secondary but essential” (No. 20).

Yet peace often seems an activity only for those who are “into that sort of thing.” Many associate peacemaking mainly with protesting war and injustice. If they know a little more, they may think policymaking. If they know even more, they may think of on-the-ground practitioners in the developing field of peace-building. But even if all these associations are positive, peacemaking can still seem like other people’s business. Protest requires a certain disposition. Policymaking requires expertise. Peace-building practitioners need training in techniques like conflict resolution.

Yet peace often seems an activity only for those who are “into that sort of thing.” Many associate peacemaking mainly with protesting war and injustice. If they know a little more, they may think policymaking. If they know even more, they may think of on-the-ground practitioners in the developing field of peace-building. But even if all these associations are positive, peacemaking can still seem like other people’s business. Protest requires a certain disposition. Policymaking requires expertise. Peace-building practitioners need training in techniques like conflict resolution.

Pope Francis would change this by widening our focus in a way that places every vocation, technique or tactic in the wider context of God’s overarching strategy in history.

For Francis, after all, peace-building means building a people of peace—people-building. In his exhortation, “The Joy of the Gospel,” he speaks repeatedly of all work for peace and the common good as building or becoming a people. This follows his portrayal of evangelization as the work of the entire church, which is “first and foremost a people advancing on its pilgrim way towards God,” thus opening out as “a people for everyone” and “a people of many faces.”

We may ask which people he means. That would be the wrong question.

People Within a People Within Peoples

Picture a set of nested Russian dolls. Once we recognize the work of peace-building as people-building, we start to notice that God’s own peacemaking strategy always places creative people as change agents within communities, within peoples.

That World Day of Peace 2000 message from John Paul II, for example, worked at multiple layers at once. As a sacrament of peace, the church is to be both a sign—being—and instrument—doing—of a saving reality beyond itself. But even as the nesting pattern moves outward into the world, it also calls inward to an “essential” role for each of the Catholic faithful.

The pattern is really the oldest and most basic in salvation history. In Genesis, even as God called Abraham promising the blessing of descendants who would become a great people, God’s strategic purpose for them was that they be a blessing to all other families or peoples of the earth. The elegant paradox of an Abrahamic community is that it can be true to its vocation as a people only if it is ready to risk that very identity by blessing and living for other peoples.

Francis draws instinctively on this Abrahamic pattern. The church must live its life on the streets, he insisted as he began his papacy, preferring the risk of getting wounded out there to the prospect of stagnating health from living behind closed doors. In “The Joy of the Gospel” he demonstrates the theological heft that sustains his pastoral practice. Turning midway to a natural-law mode of reflection, he lays out four principles. Together they aim to transform the social conflict and cultural diversity that are an inevitable part of human life into “a genuine path to peace within each nation and in the entire world.”

Francis’ Four Principles

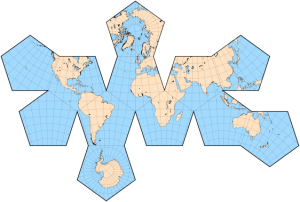

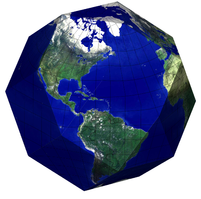

In writing his first apostolic exhortation, Pope Francis reiterates many core lessons of Catholic social teaching. But to summarize his vision, Francis ultimately turns to a fresh and suggestive image—that of a polyhedron.

Both a sphere and a polyhedron can serve as metaphors for human equality, but the first is individualistic and the second is communal. While a sphere seems to offer perfect equidistance from the center, the egalitarian justice of a sphere is deceptive, for its cost is the globalized smoothing out of all cultural differences. A polyhedron, in contrast, offers the image of a richer justice of equality through participation in local cultures that have not lost their distinctiveness.

Both a sphere and a polyhedron can serve as metaphors for human equality, but the first is individualistic and the second is communal. While a sphere seems to offer perfect equidistance from the center, the egalitarian justice of a sphere is deceptive, for its cost is the globalized smoothing out of all cultural differences. A polyhedron, in contrast, offers the image of a richer justice of equality through participation in local cultures that have not lost their distinctiveness.

Accordingly, the work of peace-building must be the very task of becoming a people of peace whose social posture in the world serves the respective cultures and common good of all other peoples. Each of Francis’ four principles builds toward this vision.

1. “Time is greater than space.” However urgent we sense the world’s needs to be, our first and most basic task as Christians is not to seize power but to generate processes of people-building, not to hold territory through frantic and domineering self-assertion but to be patient with history.

To instead give priority to time puts spaces and material goods into their proper perspective. It allows us to engage in actions that “generate new processes in society and engage other persons and groups,” allowing them the time they need to grow and bear fruit in history. All this “without anxiety, but with clear convictions and tenacity.”

The Christian horizon of action, after all, is not geographical, but eschatological. The most important location we live within is not a space we may pretend to possess, but a time given us as a gift. This is the time between the already of God’s beckoning future and the not yet of our limited human condition. To be sure, life in this in-between time presents a “constant tension.” But recognizing time as greater than space gives us “a first principle for progress in building a people.” We can live in that tension between fullness and limitation and “work slowly but surely, without being obsessed with immediate results.”

As a first principle of people-building, the priority of time over space should also blunt the besetting temptation to put nationalist loyalties above solidarity with other peoples around the globe—to say nothing of the global Christian people living in diaspora amid many nations. Robert George of Princeton University has warned that in the face of secular animosity toward Catholic teachings: “The days of acceptable Christianity are over. The days of comfortable Catholicism are past.”

One need not share all of Professor George’s alarm or his agenda in every detail to share his presupposition: The demands of Christian faith and Catholic identity are not coterminous with the moral climate and borders of the United States or any other nation-state. As William Cavanaugh and Michael Baxter wrote in these pages (“More Deeply Into the World,” 4/21), all Catholics should embrace the mestizaje that immigrant Latino Catholics model as they contribute to their land of residence while maintaining an identity that crosses its borders.

2. “Unity prevails over conflict.” In introducing his four principles, Pope Francis reiterates the teaching of the Second Vatican Council that peace is not merely the absence of violence or warfare. As the pope moves to his second principle, the implication is this: Conflict can in fact be a positive “link in the chain of a new process” of people-building, but only if it is “faced” rather than “ignored or concealed.” Facing conflict frankly, with a willingness to work for resolution “head on,” in fact makes it “possible to build communion amid disagreement.”

Such honest confrontation opens a “third way” between callous evasion of conflictual realities and resentful entrapment within conflicts. But to engage in conflict nonviolently requires a living hope that underneath our conflicts lies a more profound unity that allows us to build friendship in society and act in solidarity.

Surely such practices and hope must take shape within the church’s own communion if it is to be a “sign and instrument of peace in and for the world.” Writing in these pages, my colleague Massimo Faggioli called for rebooting Cardinal Joseph Bernardin’s Catholic Common Ground Initiative in order to facilitate dialogue and consensus-building across all levels of the U.S. church (“A View From Abroad,” 2/24). Widely practiced, the value of such a project would come not just from inviting Catholics to transcend their own culture wars. The very effort would mean that Catholics across thousands of parishes would receive training in the same skills of conflict transformation that the Catholic Peacebuilding Network has been developing around the world.

3. “Realities are more important than ideas.” Coming from Latin America, Pope Francis obviously knows the cultural self-recognition that Cervantes captured in the figure of Don Quixote. In his flights of idealism, Quixote needed the realistic Sancho Panza as a companion. Long before Jorge Bergoglio became Pope Francis, he undoubtedly knew many Latin American intellectuals advocating political ideologies who needed a dose of realism.

Pope Francis’ third peace-building principle thus speaks to both pastoral practice and politics. In the context of peace-building, that carries additional lessons. Whether coming from reformers or fundamentalists, he insists, ideas that are “detached from realities” and “dwell in the realm of words alone, of images and rhetoric” are “dangerous.”

Surely this is why peace-building for him must first of all be about people-building. One of Mahatma Gandhi’s most famous aphorisms, we might recall, was to “be the change you wish to see in the world.” Likewise, Francis insists, Christian peace-building must be incarnate.

What we offer to the world, therefore, cannot be mere policy proposals. It must be embodied in the life of the people called church. Learning to talk constructively in our parishes about effective responses to poverty, what will really discourage abortions, how to welcome immigrants, when to resist unjust wars and, for that matter, how to negotiate our disputes over liturgical matters—all contribute to world peace as surely as Vatican diplomacy.

4. “The whole is greater than the part.” Pope Francis now turns to the “innate tension” that “exists between globalization and localization.” We should neither allow the glitter of global culture to seduce us nor encase local cultures unchangeably in museums of folklore. Our challenge is to broaden our horizons even while putting deep roots down into our native places. Again, this suggests that to work for strong families, vibrant but hospitable neighborhoods and racial justice in our cities and regions is as crucial to peace- and people-building as policymaking in national capitals or mediation in war zones.

Here, then, is where Pope Francis presents his many-faced “polyhedron” as a model of global reconciled unity. The Gospel certainly embraces all people universally. But it does so through creative inculturation that sustains the cultural genius of every people and leaves no lost sheep behind. “Pastoral and political activity alike seek to gather in this polyhedron the best of each” (No. 236).

A Church for All People

As the first pope from the Global South, Pope Francis has personally experienced the globalizing forces that buffet the peoples of the world. Amid the cultural corrosions and economic exploitations that modern life accelerates, Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio learned that we should not take people-hood itself for granted. But if it is the vocation of the church as a whole to be a people-for-all-peoples, the church can build itself up as a people only through the diverse vocations of all the faithful.

Entities like the Catholic Peacebuilding Network—together with the academic peace studies departments, peace-building agencies and episcopal social justice offices it brings together around the globe—represent growing expertise. The ecumenical Just Peacemaking Initiative, led by the late Glen Stassen, has documented proven peace-building strategies. Knowing what to do for peace is less and less of a problem. What we lack are people practiced in the skills and virtues of peace-building.

Doing requires doers, after all. Peace-building requires peace-builders. Peace-builders require formation through participation in a people of peace. The Methodist theologian Stanley Hauerwas is famous for insisting that the church does not have a social ethic; the church is a social ethic. Likewise: the Catholic Church cannot be content to have Catholic social teaching; it must constitute Catholic social teaching in its very life together, church-wide and parish-deep, as a people of peace.

Gerald W. Schlabach is a professor of theology at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota and lead author and editor of Just Policing, Not War (Liturgical Press). He is currently at work on a book tentatively titled A Pilgrim People: Becoming a Catholic Peace Church.

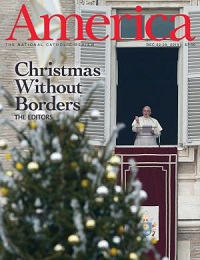

Reprinted with permission from America magazine, December 22-29, 2014, pp. 20-24.

SIDEBAR:

Building a People of Peace

The liturgical reform movement has been forming us as people of justice and peace for decades. Social justice offices in parishes and dioceses have forged numerous projects to develop and practice global solidarity. Pro-life organizations walk with struggling families and women to protect the unborn.

What we can do better in response to Pope Francis’ vision of people-building is to enact the liturgy and tell the story of God forming a people of peace down through the centuries in ways that draw all our projects, vocations and lives together. Here are some suggestions.

Liturgy and Preaching

• The prayers of the people at Mass should always balance local concerns with global solidarity for the church around the world. If we pray for “our troops,” we must also pray for conscientious objectors and above all—as Jesus taught—for enemies.

• Attend to the liturgical message of flags: The U.S. flag should never stand alone in our liturgical spaces. Either move it out of the sanctuary or add flags from many countries of origin of parishioners and ethnic groups in one’s diocese.

• Longer-term, bishops and liturgical commissions should consider revising eucharistic prayers in order to underscore how the nonviolent character of Christ’s passion is normative for all disciples, as the Rev. Emmanuel Charles McCarthy (centerforchristiannonviolence.org) has advocated.

Catechesis and Catholic Higher Education

• Homilies should offer more than therapeutic spiritual counsel. They should draw out the invitation that the church year and indeed every Eucharist already embodies—to join in the drama of salvation history by which God has been forming a people blessed to be a blessing for all the peoples of the earth through service to the common good of all humanity.

• In parish settings and Catholic educational institutions, young people should learn the dynamics of active nonviolence and the criteria of the just war tradition, so that any Catholic support or participation in warfare is truly an exceptional last resort.

• Longer-term, the work of theologians should solidify and popularize the proper Christian historicism that the Second Vatican Council reaffirmed, thus inviting all the Catholic faithful to recognize their lives and vocations as participating in God’s saving work here and now, even as it promises eternal fulfillment beyond this life.

Community Formation and Social Action

• Pick up on a suggestion that Archbishop Hélder Câmara of Brazil once made as part of his ringing call, “Abrahamic minorities unite!”—namely, form small affinity groups among professionals for reflection, mutual counsel and joint action to direct their vocations toward true social transformation favoring the poor at home and around the world.

• Support organizations like the Jesuit Volunteer Corps and Maryknoll Lay Missioners so that offering two or three years of dedicated service might one day become as normative for Catholic young people as it is for Mormons.

• Continue developing “sister church” relationships among parishes not only across continents but also among parishes with different racial, ethnic and class identities in our own dioceses.

• Bring home the pioneering work that the Catholic Peacebuilding Network has been doing to learn and teach conflict transformation capacity in war-torn areas of the world by offering similar parish- and diocesan-level training in the skills needed to transform our own relationships amid American and Catholic “culture wars” into models of creative civility. —G.W.S.